Prohibited Conduct Explained for Debt Collectors

🕒 6-minute read

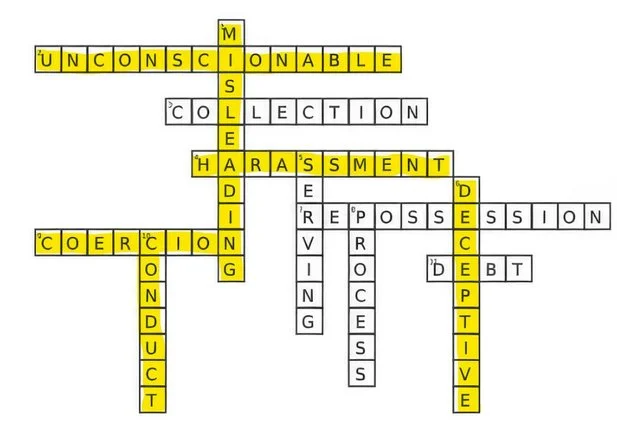

Understanding Harassment, Coercion, Unconscionable Conduct and Misleading Behaviour in Debt Collection and Repossession Work

Introduction

If you work in debt collection, repossession, or process serving, knowing the difference between harassment, coercion, unconscionable conduct, and misleading or deceptive conduct isn’t just semantics—it’s critical to staying compliant and protecting your professional reputation.

We regularly see students in our CPD compliance training struggle to distinguish these terms. That’s understandable. In everyday conversation, they often overlap. However, in the world of credit, collections, and field work, each term has a specific legal meaning—and real consequences.

Getting them wrong can breach the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), the National Consumer Credit Protection Act (NCCP Act), or guidelines established by the ACCC and ASIC. It can also lead to complaints, fines, or disciplinary action.

This article breaks down each concept with examples to help you apply the proper standards in the right situations.

Four Words — Four Legal Risks

| Term | Key Feature | Legal Source | Common Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harassment | Repeated, unwanted contact or threats | ACL, NCCP Act, Privacy Act, ACCC/ASIC Guideline | Calls, texts, emails, visits |

| Coercion | Using pressure to force a decision | ACCC/ASIC Guideline (informed by ACL) | Threatening consequences to extract payment |

| Unconscionable Conduct | Taking unfair advantage of someone | ACL ss 20–22, NCCP Act, ASIC Act s 12CB, case law | Exploiting distress, disability, or power imbalance |

| Misleading or Deceptive Conduct | False, unclear, or incomplete information | ACL s 18, NCCP Act, ASIC Act s 12DA, ACCC/ASIC Guideline | Misstating obligations or legal processes |

Harassment: When Contact Crosses the Line

The Debt Collection Guideline defines harassment as behaviour that causes distress, humiliation, or intimidation through excessive or unreasonable contact.

The law doesn’t ban contact—but it limits how often, how intensely, and in what manner.

Examples of harassment:

- Making more than three calls, visits, or messages per week without consent—especially when contact becomes persistent or upsetting

- Calling outside standard hours or contacting someone at work after being asked not to

- Using aggressive, sarcastic, or belittling language

- Repeated visits despite a formal dispute or request to stop

- Publicly disclosing the debt to neighbours or employers

Harassment isn’t always verbal. Silence, body language, surveillance, or loitering can also breach the line.

“A debtor is entitled to be free from excessive or unreasonable contact... even if the contact is made politely and without threat.”

— Debt Collection Guideline

Think of it this way: Harassment is like knocking on a locked door—again and again and again. It’s not what you say; it’s how often, how hard, and how long you refuse to stop.

Coercion: Using Pressure to Get a Result

Coercion means pressuring someone into a decision they wouldn’t otherwise make. It’s not confidence or assertiveness—it’s manipulation, and it’s unlawful.

Examples:

- Threatening legal action or repossession without genuine authority or intent

- Using family or employer pressure to force payment or surrender

- Physically intimidating someone to sign a document

- Using silence, stance, or presence to corner someone into saying “yes”

In ACCC v Excite Mobile Pty Ltd (2013), the court found coercion when customers received letters threatening legal action—even though no enforceable debt existed.

Think of it this way: Coercion is like backing someone into a corner. It’s not a choice if there’s no safe way out.

Unconscionable Conduct: Exploiting Vulnerability

Unconscionable conduct involves taking advantage of someone who is vulnerable, uninformed, or disadvantaged in a way that offends community standards of fairness.

It’s outlawed under:

Warning signs:

- Using legal jargon or rushed pressure to confuse someone

- Ignoring signs of distress, language barriers, illness, or grief

- Denying a person time to seek advice or clarify options

- Taking advantage of trust, urgency, or emotional stress

In Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd v Amadio (1983), the High Court found that elderly parents had been misled and exploited. The conduct was ruled unconscionable.

Think of it this way: Unconscionable conduct is like taking the wheels off someone’s car, then blaming them for not getting to work. You’re punishing someone for a position you’ve unfairly created.

Misleading or Deceptive Conduct: Twisting the Truth

Under ACL s 18 and ASIC Act s 12DA, misleading or deceptive conduct is illegal—even if it’s unintentional.

If your words or actions lead someone to believe something that’s not true, or leave out key facts, you could be in breach.

Examples:

- Telling a customer that legal action has started when it hasn’t

- Suggesting repossession is guaranteed if payment isn’t made immediately

- Overstating debt amounts, fees, or legal outcomes

- Saying “you have no rights” or “you can’t stop this” without a proper basis

Even partial truths or omissions can mislead—this includes scripts, emails, texts, letters, and conversations.

Think of it this way: Misleading conduct is like when you install a road sign that points the wrong way. Even if you thought it was right at the time, anyone who follows it ends up off track — and you’re still responsible for where it led them.

Overlap Happens

In practice, these behaviours often appear together. For example:

A field agent visits a customer five times in one week. On the fifth visit, the agent says, “The car will be repossessed today no matter what,” and fails to mention that legal consent (Form 13) is required to remove the vehicle from the premises. The customer is recovering from surgery and is under financial stress. In this single event, you’ve got:

- Harassment (excessive visits)

- Coercion (implied threat)

- Unconscionable conduct (exploiting illness and stress)

- Misleading conduct (omitting legal process)

Third Parties and Privacy

Contacting third parties—like relatives, employers, or neighbours—without consent can breach privacy laws and professional standards.

Under the Privacy Act 1988 and Australian Privacy Principles (APPs), revealing personal financial information is strictly limited.

Collectors, repossession agents, and process servers must never:

- Disclose a person’s debt to others

- Leave voicemail or written messages that expose their legal or financial status

- Use third-party contact as pressure or leverage

Doing so could also constitute harassment, coercion, or misleading conduct, depending on context.

✅ Checklist: Staying Compliant

- Stick to lawful contact limits

- Never exaggerate legal outcomes

- Look for signs of distress or confusion

- Don’t rush or pressure someone into signing

- Be honest and complete in all communication

- Don’t use urgency unless truly necessary

- Respect third-party boundaries and privacy

- Keep accurate and lawful records

Ask yourself: Would this stand up in court—or on the front page of tomorrow’s paper?

Conclusion

Harassment, coercion, unconscionable conduct, and misleading behaviour aren’t just bad practice—they’re legal breaches that damage trust and expose your agency to real risk.

If you work in debt recovery, repossession, or field services, compliance isn’t optional—it’s the job. The best agents don’t guess where the line is. They’ve been trained to know.

At Beebox Training, that’s precisely what we do—deliver compliance and CPD training for debt collectors, repossession agents, and process servers who want to do the job right.

Nick’s Bio

Nick Boyd is the founder of Beebox Training, a leading provider of debt collection and repossession agent training across Australia. With over 24 years of experience in the mercantile agent industry, Nick has designed specialist compliance CPD programs for field agents, collectors, and process servers. His career spans roles as a soldier, crash investigator, and agency GM, giving him real-world insight into enforcement work and legal obligations.